A Love Letter to Protestantism

And, The Theology of Contemporary Christian Music

While defending Protestantism to the friend who would eventually become my godfather,1 I once found myself saying that Evangelicals are the only people on earth ready for Jesus to look entirely ordinary. And I was right. Although I hope, pray, and work for the reunification of all Christians under the Vicar of Christ, I am not an undiscriminating warpath against the community that first taught me to love the Lord.2 On the contrary, Protestantism, especially Evangelicalism, has so much good that I am anxious to protect and multiply its rich harvest. “Not to abolish but fulfill.”

From Catholics who feel a blanket distrust of anything that comes out of Protestant Christianity, I ask a hearing. From Protestants who feel the Catholic Church just doesn’t exude Christ the way she ought, I ask an open mind. Overcoming the impasse will require us to reject the caricatures and false dilemmas constantly pushed on social media. After all, one of the most basic moves in Catholic theology is “both/and,” that is, showing that two apparent opposites can not only be reconciled, but elevated beyond their natural limits when brought together by grace. We are the Church that Baptized Plato, Aristotle, and Avicenna—surely we can Confirm some of the Protestant giants. To that end, I want to pause and reflect on what makes Evangelical Protestantism so great.

Tell an Evangelical that his love for Jesus borders on obsession, and he’ll be disappointed, as he had hoped to cross the border long ago. When I think of Evangelical spirituality, I think of fire. If “our God is a consuming fire,” they say, so much the better; “He must increase and I must decrease.” No one says it better than the man himself, Toby Mac:

What will people think when they hear that I'm a Jesus freak?

What will people do when they find out it's true?

I don't really care if they label me a Jesus freak

There ain't no disguisin' the truth

There is a single-mindedness to Evangelicalism. It systematically produces people willing to sacrifice time, energy, and money to accomplish God’s work. One could call them “mission-driven,” provided “driven” carry the sense Mark employs when he describes Jesus as being “driven out” into the wilderness by the Holy Spirit, teeming with an untamable energy. More than any other book of the Bible, Evangelicals embody Philippians. They are a people of decisive action, who feel the words of St. Paul in their bones: “Forgetting what is behind and straining toward what is ahead, I press on toward the goal to win the prize for which God has called me heavenward in Christ Jesus.”

I tend to use “Evangelical” interchangeably with “serious Protestant Christianity.” I probably conflate these two because I have spent my life in highly secularized areas, where denominations either don’t exist in any robust way (the Pacific Northwest) or continue only as atrophied institutions more concerned with keeping up with the times than converting them to the Gospel (The Northeast).

Yet there are serious denominations left, although they are shrinking. I recently visited a friend at a Christian Reformed Church seminary and was delighted by a glimpse into a world I was never really part of: the Protestantism of old, in love with the Bible and exuding a kind of quiet, unflappable strength that evidences decades in service to the Lord. I am reminded of Luis Bouyer’s remark in The Spirit and Forms of Protestantism that Calvinism, in its own way, expresses the highest mysticism. It pays gravest attention to the God who speaks in Sacred Scripture, full of the holy awe befitting one who expects to hear the voice of his Creator. Where Evangelicals burn, the children of Geneva are like glaciers gliding serenely, inexorably, gracefully across the land.

Hot or cold Protestants may be—but never lukewarm. Above all, they abhor spiritual mediocrity. Despite suspicion of any role for good works in the drama of our redemption, they zealously pursue a life worthy of the name “Christian.” (I note in passing the irony that Catholics, who are constantly accused of promoting “works-based salvation,” are not the ones with a work ethic named after them.) Although most Protestants would be instinctually repulsed by French novelist Leon Bloy’s famous observation that “The only real sadness, the only real failure, the only great tragedy in life, is not to become a saint,” the whole Protestant spiritual life reflects this thought exactly. This is the key to understanding Contemporary Christian Music (CCM), the genre that embodies the best (and worst) of today’s Protestantism, both Evangelical and traditional.

Dionysius the Areopagite was a fifth-century theologian and mystic who, despite being one of the great fountainheads of Christian thought, remains unknown to the vast majority of Christians today. Much could be said about him, but I want to dwell on one idea from his short, mind-bending treatise, Mystical Theology. In this work, Dionysius develops the idea that to reach God, we must be brought outside ourselves, past the limitations of finitude. He calls this ekstasis, from ek-, “out” and -stasis, “being.” We must go “beyond being.” Through prayer, contemplation, and ultimately the condescension of God, we are raised into the heavenly places, and although we do not see God as He is in Himself (our vision remains “through a glass darkly”), we get closer than we otherwise could in this life.

The best of CCM always tends towards the language of ekstasis. We don’t have to go farther than the all-time greatest hits to find ready examples. Here’s a bit from “Oceans.”

Take me deeper than my feet could ever wander

And my faith will be made stronger

In the presence of my Saviour

Suppose someone were to ask, “Why can’t your feet wander any deeper?” The answer would be twofold: first, because of sin, and second, because even sinless creatures remain created things, naturally limited. It will take the intervention of God to bring us any farther. This happens when Christ makes Himself present to us, both spiritually and (although the writer certainly did not intend this) in the Eucharist, where we receive the full body, blood, soul and divinity of the Almighty. Christ enters into us so we may exit ourselves. He becomes a passage for us into a wider space, into the heart of God.

“Great Are You Lord” picks up a similar theme

It's Your breath in our lungs

So we pour out our praise to You only

All the earth will shout Your praise

Our hearts will cry, these bones will sing

Great are You, Lord

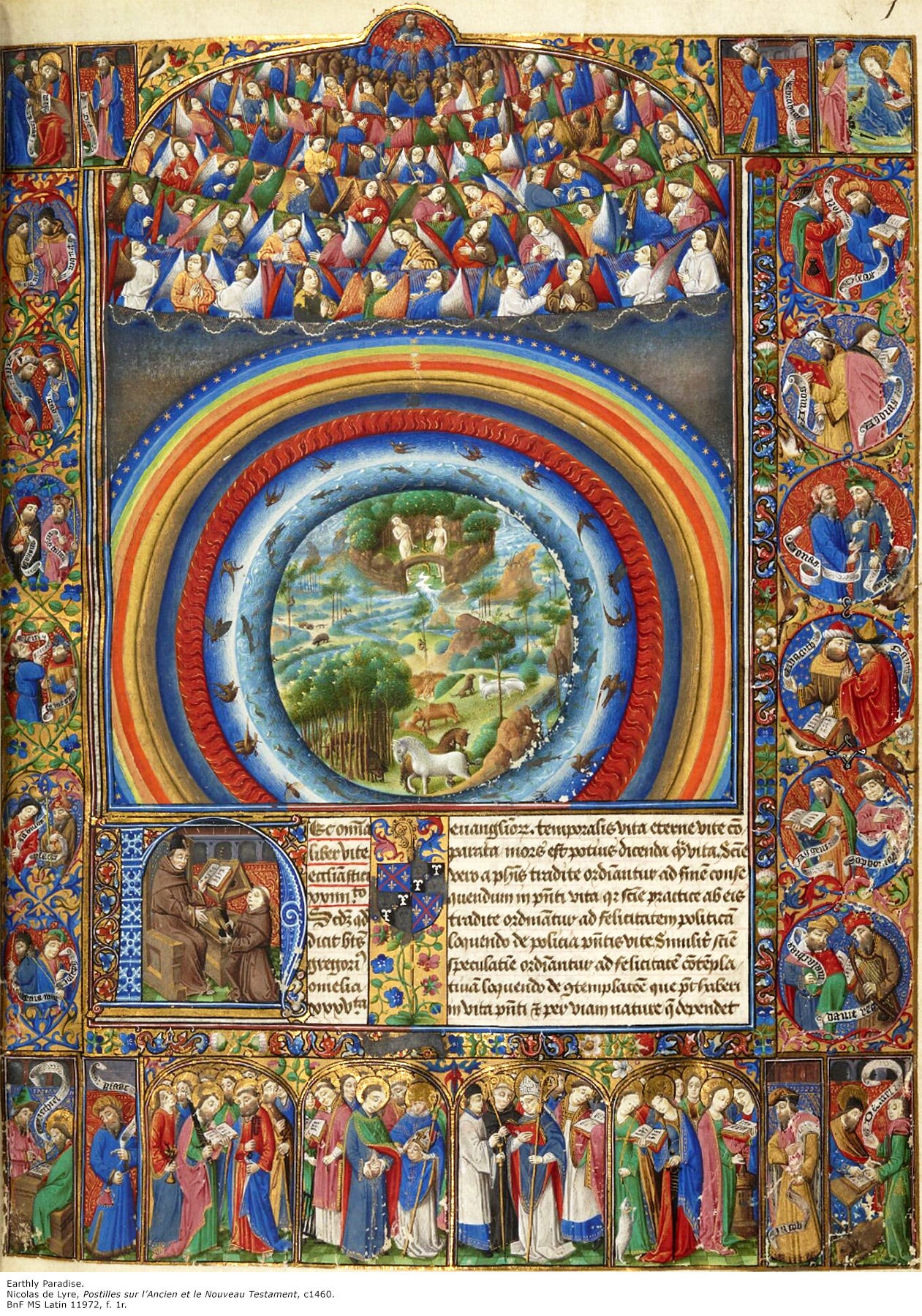

While this song doesn’t bring out the theme of ekstasis quite as overtly as “Oceans,” it isn’t far below the surface. It’s easiest to notice when sung with hundreds of others, the music swelling as these lines are repeated again and again, each repetition seeming to pick up first men, then beasts, then plants, and finally every rock and hill, so that all creation joins together in a pure chord that is perhaps best described as the interstellar melody the ancients called “the music of the spheres.” We are lifted out of ourselves into a universal hymn of praise. Dionysius calls this theme exitus et reditus, “exit and return.” God creates us at somewhat of a distance from Himself precisely so that, through the charity given us by the Holy Spirit, we may have the joy of “returning” to Him, closing the circle of loving communion and renewing its course.

The obvious danger here is that a genuine expression of ekstasis is easily confused with or (worse) devolves into mere sentimentality, so that what ought to guide you beyond yourself only becomes a morbid desire to have a certain experience or feeling. No doubt, that happens often enough; though not as often as outsiders assume. In any crowd there is probably a mix. But simple sentimentality is too thin an explanation to anyone who has really lived what I’m describing. A mentor from my high school days once recounted an evening when he had gathered to sing worship music with a few dozen others. As they sang, they lost track of time completely. When someone finally checked their phone, they found they had been singing for more than four hours (and missed about a million concerned calls). They had been drawn outside themselves, or perhaps let into somewhere better. Moments like this make it easy to believe that “the earth will soon dissolve like snow.”

The point of this excursus is to show that to be Protestant is to desire ever-deeper communion with God. That is the positive element. But there are negative elements too, and it is the great, tragic irony that where one would naturally expect this to spill over into a fanatical devotion to the Eucharist, or at least an acknowledgment that if Christ were incarnationally (and not merely spiritually or symbolically) present in the Eucharist it would be a grace surpassing all expectation, there is nothing. Seen from the vantage of Catholicism, the healthiest expressions of Protestantism resemble a man with perfect command of the English language, except that he doesn’t know any of the words beginning with “P.” If he’s been getting along just fine, it may be hard to convince him that something’s missing—but once he sees the gap he’ll promptly become profoundly more proficient than previously possible.

While I’m on the topic of Protestant worship music, I want to note the constant trend of Protestant music since the Reformation to re-evolve sacred music. “Sacred music” is music designed expressly for formal, corporate worship. (I would say “liturgical” worship but it’s hard to see how most nondenom services could be called liturgical.) Although a great deal of CCM is indistinguishable from the pop of whatever decade it was produced in, this is not always the case. In fact, there are a handful of genres that serve as a kind of home-gown Protestant sacred music. Black spirituals come to mind, as well as black Gospel choir. Classical Protestant hymnody also has identifiable characteristics—one would not confuse “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God” for anything other than a religious hymn, even if the words were unintelligible. In CCM, there are hits I can’t imagine being mistaken for pop—“10,000 Reasons” comes to mind, as does “What a Beautiful Name.” The tendency to evolve and re-evolve sacred music shows two things. First, it is evidence of a genuine religious impulse, an oft-unconscious craving for the sacred, the sense that the things of God should be set apart. Second, it shows that belonging to Christ, even in the Christian communities farthest from His Church, implants in us a longing for the Mass. To be sure, few if any Protestants will agree with this second claim, but that is to be expected.

My love letter ends with three pleas.

To Catholics: We will not make headway in restoring our separated brethren to full communion if we refuse to take them seriously. We have to see the wonderful things God is doing among them, and do our best to carve out space to preserve as much of it as possible within the Church. Not uncritically, of course, but not straying into aesthetic jingoism, either.

To traditional Protestants: I fear that your spiritual legacy is disappearing from the face of the earth. The Church has shown by her creation of the Anglican Ordinariate that she is not only open to dialogue but ready to act. Having seen the destruction of your traditions both in America and Europe (I am thinking of the near-complete failure of Lutheranism in the Scandinavian countries), you must know that Presbyterians, Anabaptists, Methodists, and any other denominations hanging on to life bear the divine promise of preservation no more than the Puritans did.

To Evangelicals: You will no doubt continue to grow in the decades to come, and God be praised for every person you help bring to Christ. But the things you build—can they last a hundred years? A thousand? Ten thousand? Or will they welter in pastoral anarchy until they finally collapse? The quality of our work will be revealed by fire; and if we have built from wood and straw, we will suffer loss. We have a duty to the souls of this generation, certainly. But we also have a duty to the generations yet unborn. We can’t just build our own little huts. We have to work together if we want to build cathedrals again. That can only happen if we are one in faith, and sacrament, and pastoral leadership. And there is only one Church with a credible claim to universal headship.

I suspect I’ve made everyone a little bit mad. Well, that’s what a good love letter does.3 I also suspect some (like myself) are prone to feel despair when they think about movements at this scale, like a snowflake trying to stop an avalanche. Take heart! The Church may have to wade through hell on her pilgrim journey—but Christ has promised that she will not end there.

< Baptists: Word and Zeal | Building Reformation Catholicism | F.A.Q’s >

A person receives godparents when they are baptized. Godparents are responsible for looking after the spiritual wellbeing of the one being baptized, and promise to help them grow to full maturity in faith with time. Although the Catholic Church recognizes any correctly performed baptism, we discovered a hiccup with the “baptism” I’d received in second grade, a hiccup significant enough to invalidate it. As a result, I had to be baptized “again” (really for the first time), and since it was a Catholic baptism it came with godparents. As a result, I had the honor of asking my dear friend Marcus Gibson to be my godfather.

Though I admit I must qualify my admiration for this trait with a passage from Lewis:

I think the "low" church milieu that I grew up in did tend to be too cosily at ease in Sion [Amos 6:1]. My grandfather, I'm told, used to say that he "looked forward to having some very interesting conversations with St. Paul when he got to heaven." Two clerical gentlemen talking at ease in a club! It never seemed to cross his mind that an encounter with St. Paul might be rather an overwhelming experience even for an Evangelical clergyman of good family. But when Dante saw the great apostles in heaven they affected him like mountains. There's lots to be said against devotions to saints; but at least they keep on reminding us that we are very small people compared with them. How much smaller before their Master?

Just kidding. Let the reader be advised that this is indeed not a template for a successful love letter. Even if it were, the overlap between “people this kind of writing could effectively woo” and “people dedicated to a life of celibacy” has got to be nearly complete.

I would love to read a reply from or dialogue with a committed Evangelical.